This guest post is by Elaine Blackman, Writer/Editor for the Office of Child Support Enforcement, Department of Health and Human Services.

Cleaning up our language: A never-ending campaign

Only a few generations ago, many causes and movements set out to clean up the environment. Do any of you remember the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign? Over time, most of us have learned the habit of throwing trash in a trashcan—not on the street. We changed our behavior thanks to research, education and laws, and creative messaging about pollution, litter, and pride in our surroundings.

It may be hard to believe that campaigns to end “gobbledygook”—bureaucratese, difficult-to-understand language—has been underway for just as long, if not longer. In 1962, a government Clear Communication Newsletter advised workers to leave out “every effort will be made,” “experience has indicated that,” and “this is to inform you” from their writings.

Yet, despite research, education and laws to inspire plain language in government and business writing, many long-timers still set an example to newcomers that complex jargon is OK. By not writing in a clear, concise and organized manner in our emails, letters and web media, we continue to cause a different kind of litter—confusion and inefficiency.

The same reasoning applies to speeches; we want to find shorter, stronger words to engage our audience. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt did when his speechwriter gave him this weak sentence: “We are endeavoring to construct a more inclusive society.” FDR made the message more powerful: “We are going to make a country in which no one is left out.”

Not easy being green

We know that changing environmental habits isn’t easy; neither is changing writing habits. However, the good news is we are improving. On July 19, the Center for Plain Language issued the Plain Language Report Card for 12 federal agencies on their progress in meeting the Plain Writing Act of 2010. Who got an A? USDA! Not too shabby for HHS though; we got a C in “basic Act requirements,” such as having a plain language official, an implementation plan, and training for employees; and a B for a variety of “supporting activities” in the “spirit” of the Act.

The same organization announced the 2012 ClearMark Plain Language Award, in June, given to the best plain language documents and websites in both public and private sectors. HHS claimed several wins, for the FLU.gov website and several “before and after” forms and publications, to name a few. Check out the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Outdoor Air Quality site; they did extensive user testing.

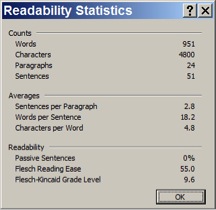

In my HHS agency, we help state, tribal and local programs deliver quality child support services to parents and families, so the material we post daily on our new Child Support Services website must display plain language and design. We have a long way to go to convert the older documents on the website into plain language. On the other hand, we’ve begun to train our staff in plain language skills. In our training, we edit real child support program writing samples. We also learn about a readability tool in Microsoft that gives the grade level of our document and a readability score from 0 to 100, with 65 considered the plain language target—and it’s not an easy reach. The score for this article: 55.0, with 0% passive sentences, another benchmark for easy reading.

In my HHS agency, we help state, tribal and local programs deliver quality child support services to parents and families, so the material we post daily on our new Child Support Services website must display plain language and design. We have a long way to go to convert the older documents on the website into plain language. On the other hand, we’ve begun to train our staff in plain language skills. In our training, we edit real child support program writing samples. We also learn about a readability tool in Microsoft that gives the grade level of our document and a readability score from 0 to 100, with 65 considered the plain language target—and it’s not an easy reach. The score for this article: 55.0, with 0% passive sentences, another benchmark for easy reading.

Will the two-hour trainings suffice to change old writing habits? For most, the answer is no. Sure, some are taking plain language seriously; others, however, seem to think that plain language means “dumbing down” our writing to appease a few. Nothing could be further from the truth—writing in plain language means “smartening up” to engage the masses!

So, it will take a lot of practice and willingness for staff to write for the web so that readers can easily scan. We need to use active voice and short paragraphs, omit long lead-ins and wordiness, and stick to certain formats—always keeping our wide-ranging audience in mind.

What’s in it for me?

The way we communicate is like the old adage “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” If we want to receive clear and concise messages that we can understand the first time we read them, then we should write to others that way. Plain language benefits readers and writers. “It doesn’t just cut reading time, it also saves you and your readers time and money,” according to the website PlainLanguage.gov, which cites examples and offers the Federal Plain Language Guidelines.

If you would like more references to share with your coworkers, look at a brief slide presentation by the Federal Communicators Network, Introduction to Plain Language. Are you familiar with the National Association of Government Communicators? It offers an annual “Communications School” and cosponsors training events around the country for members and nonmembers from every level of government. In fact, search the Internet for “plain language,” and you will find a movement filled with examples for every field.

When we put internal communication first, employees will understand the culture and necessity of plain language. Then, we will go further to enhance our program brand and external communications. Moreover, it will be obvious to anyone who visits our website or works with us that we treat everyone as we would like to be treated, using plain, simple and culturally appropriate language. We want our messages and our conversations to be as clear and concise as we can make them.

Which sentence sounds better to you?

After a thorough review of your report, this office approves the recommendations.

Or …

We approve your recommendations.

(Do you approve of mine?)

Thanks for the guest post, Elaine!

If you’d like to write a guest post for the Writing Matters blog, contact me at Leslie@ewriteonline.com. Interested in other plain language posts on the Writing Matters blog? Check out “If I told you to containerize your branches, would you know what to do?” and “Your Honor, could you repeat that … in plain language?”

Tags: Plain language

0 Comments